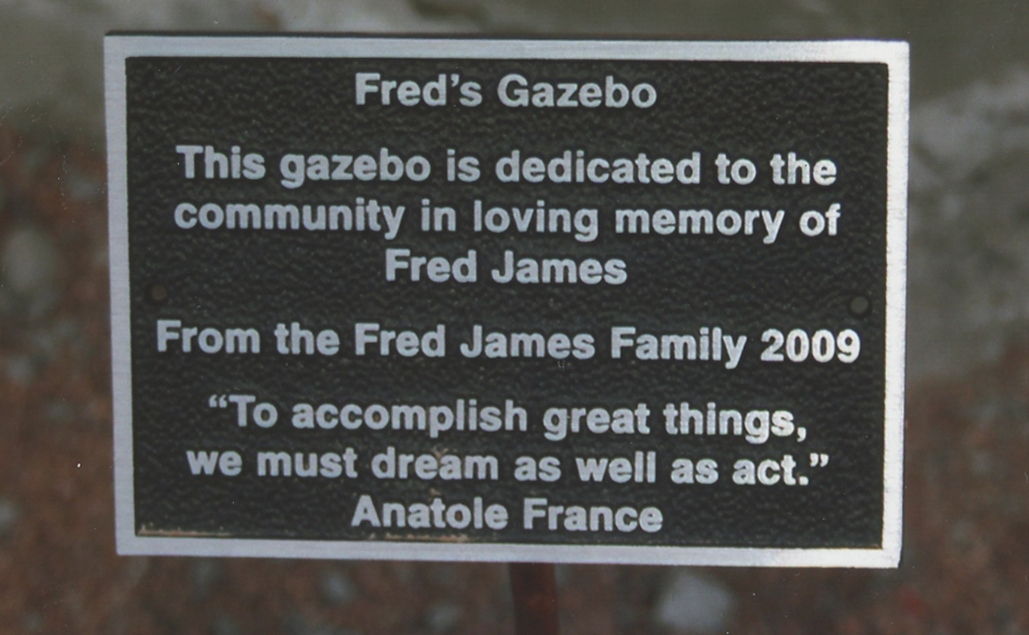

My miniature painting In Memoriam is a tribute to my father, Fred Keith James, who passed away on January 23, 2001. The flowers in the painting were given for his funeral. Dad’s passing was no tragedy as he had lived a full life; nor was it a surprise as he had been suffering from health problems for years; and as a person of faith, I know he is in a better place. But, I miss him.

Not an outwardly sentimental man, Dad had no difficulty in expressing his love and his support for others through his actions. This is a man who, every year on his own birthday, would send a dozen red roses to his mother.

There was something in Dad that inspired him to start “new” traditions like the roses. However, on occasion, they created unforeseen repercussions such as when the neighborhood kids asked their parents why the Valentine Man did not visit their homes. We had a basket where we were to place all the Valentines we received from school and in the mail. At some point, they would disappear. Later, the doorbell would ring, and no one would be there…just this big sack on our porch full of Valentine cards, including new ones and lots of Valentine candy for the whole family. In a way, it made the little cards we exchanged at school even more interesting as we spread them out and read them again. Complaints from the other parents meant the Valentine Man was forced to retire after only a couple of years, but the memory of it still lingers with me every February 14th. Dad did not voice his emotions, but his love and care could not be clearer.

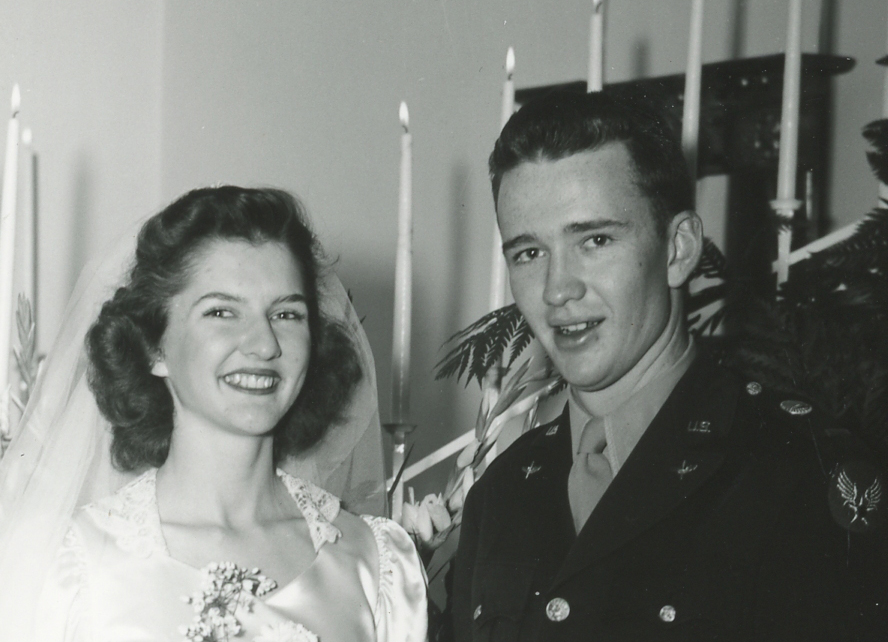

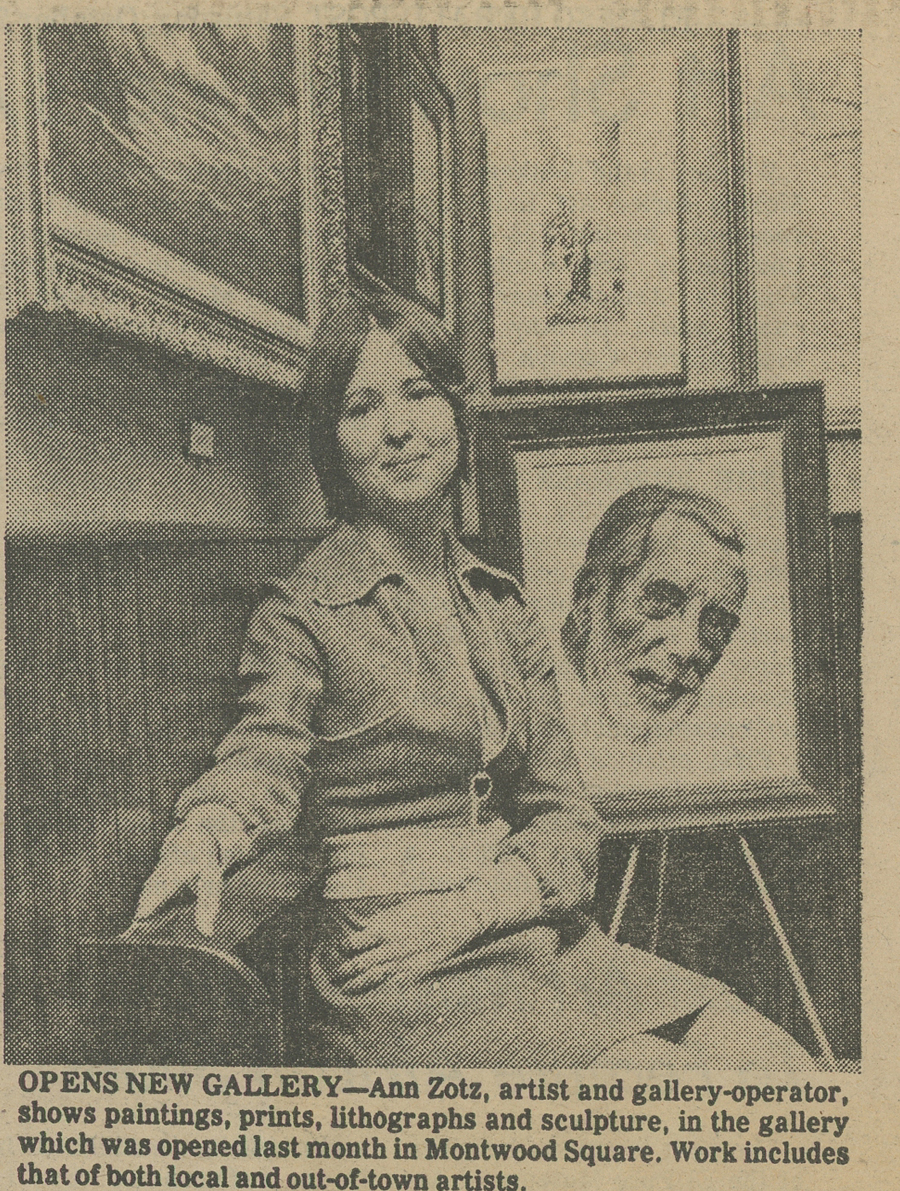

His support for me and my art was inspiring. In 1974, when I was twenty two years old, I was married, living in San Antonio, and working happily as an executive secretary for a heavy construction equipment company. Already I was entering a few art competitions, winning awards and receiving commissions. However, my husband was dissatisfied with his job at the public utilities company. With the optimistic bravura of youth, I finally told him, “Ok, you and I are going to quit our jobs, we will move to El Paso, you will go to UTEP and get your degree to realize your dream of becoming a baseball coach, I will open an art gallery and pursue my dream of becoming a professional artist, and we will live with my parents until you graduate.” He thought it was a fine idea. So I called my parents and told them my “brilliant” plan. Most parents might ask, “Are you crazy?!!!!” My father said, “I know the perfect place for the gallery.”

Although Dad was an engineer by profession, he had many abilities and interests that directly impacted my art. He was a marvelous photographer, a talent that helped pay his way through Northwestern University. Before I was ten years old, my father taught me how to develop my own black and white photos in the darkroom he built in our basement. There I learned the basics of composition and design and developed a passion for value that certainly contributed to my immediate success with the wax pencil. In addition, many of my early pieces were directly inspired by Dad’s photographs of our large family (I have four siblings). For twenty years, he, in turn, photographed my drawings, providing me with excellent permanent records of my work, an absolutely essential element of any successful art career.

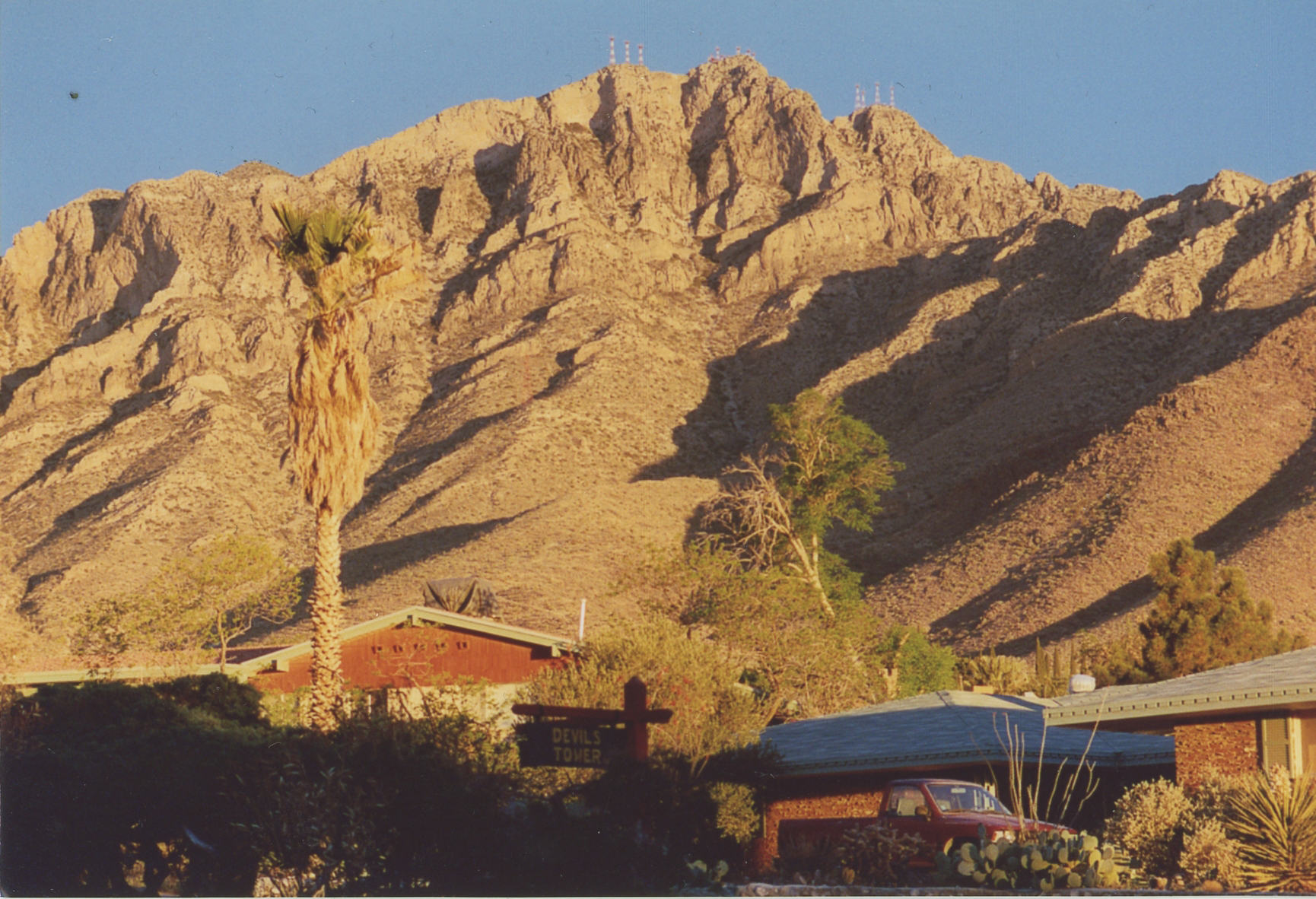

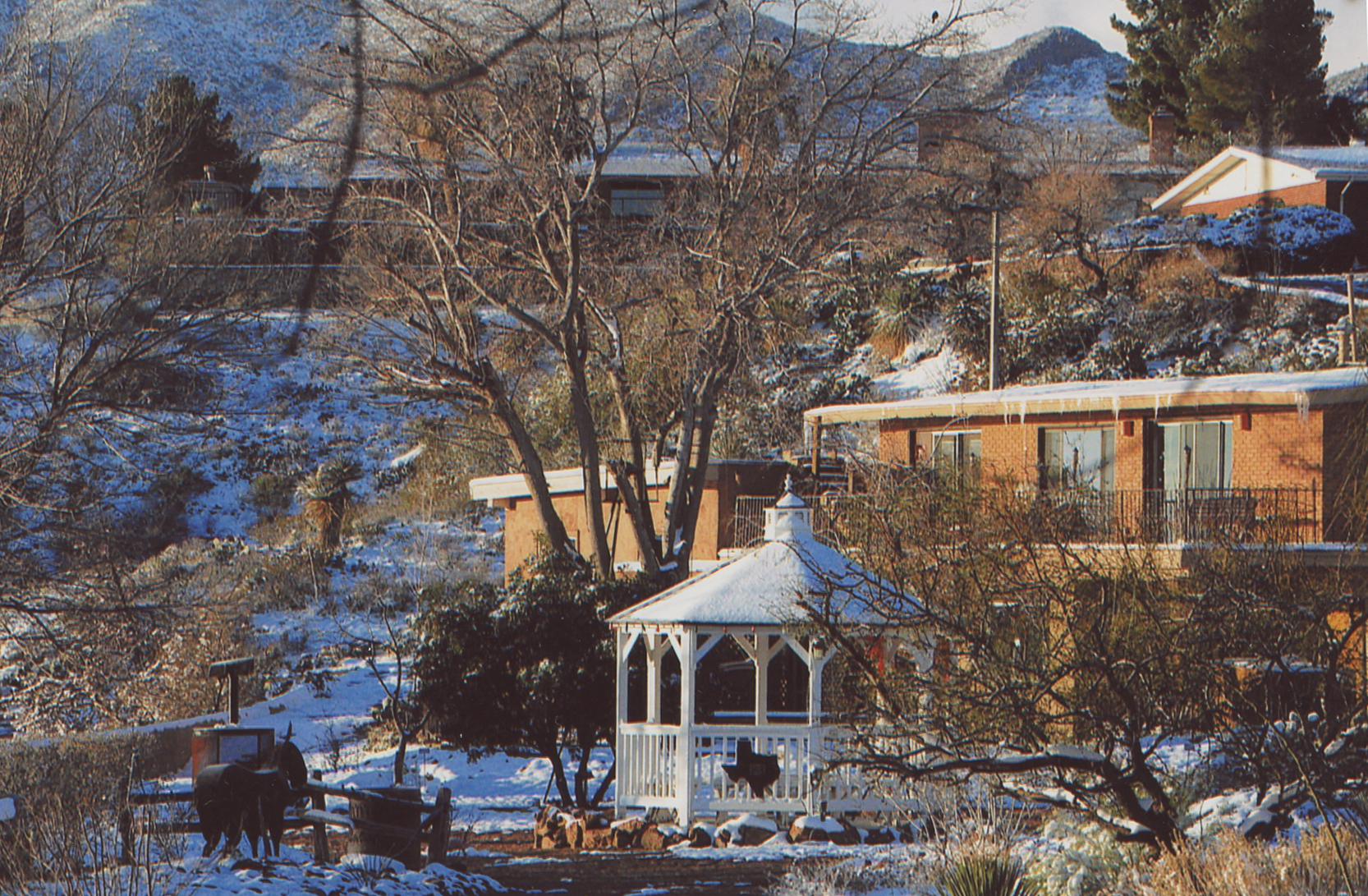

Our basement held more than Dad’s darkroom. He created the most amazing train town that appealed to the kid and engineer in him as well as to all of us and our friends. It also contained his workbench and shop where he taught us all how to make our own arrows. Dad stacked three hay bales with a target at the bottom of our property in the arroyo and we would shoot from our back patio. My oldest brother Frank even started his first business, James Archery, selling arrows to Western Auto, the local hardware store, as well as to the neighborhood kids who competed for inexpensive trophies he bought. With the undeveloped side of Devils Tower as the backdrop, any arrows missing the target slid up the rough desert terrain, creating a constant need for repairs or new arrows. I still have my bow, my quiver and a few arrows left that I made when I was a youngster.

©1999 Ann James Massey

The workshop was more than for just making arrows. Dad loved to work with his hands and he was a splendid carpenter, filling our home with his bookshelves, cabinets and built-ins. When I decided to try the art show circuit for a while in the early 1980’s, Dad even built me a portable booth that I could load in the back of my small hatchback and put up and break down with relative ease. About ten years after that, he made lovely, simple music boxes for his three girls; Mom, my sister Susan, and me. That gift is with me in my studio in Paris and is portrayed in my paintings La Maison de Poupées and The Blessing of the Animals.

Even more than that representation of Dad’s creativity and caring, my father is literally a physical presence in all my paintings. In 1990, after twenty years of drawing, I found the old master’s painting technique I had been searching for. Instead of working on canvas or masonite, I preferred using sapele mahogany boards. This was no easy task because the boards had to be cut from large sheets of mahogany plywood and then individually coated with three layers of rabbit skin glue and two layers of whiting, allowing considerable drying time and sanding between the layers. Dad immediately volunteered to take on the time-consuming project, making me dozens of boards for my painting.

During his final illness in the hospital, and though he was hardly able to speak after being taken off the respirator, Dad looked up at me and the first thing he said was, “Do you need any more boards?”

Photo © 2006 Ann James Massey

Photo © Ann James Massey