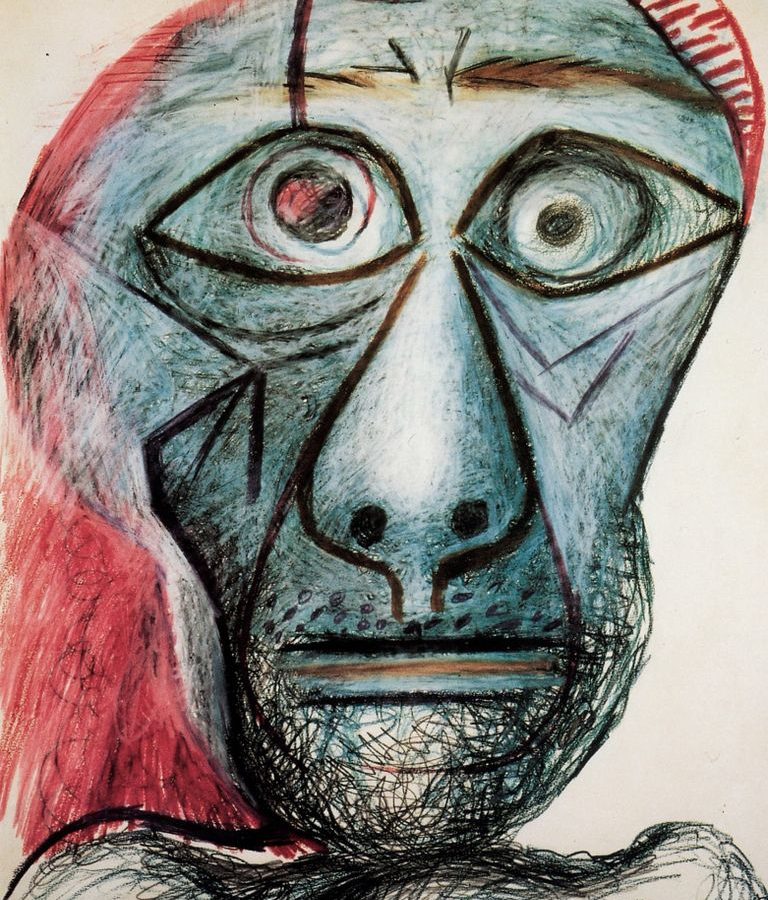

The release of my nude drawings, “Liz II” and “Liz III” as limited edition prints by Solomon & Whitehead, Ltd. in England presents the perfect opportunity to take a fun quick glance at the nude in art.

Since the dawn of man’s creative powers, artists have felt the need to depict the human form. Prehistoric sculptures were fertility symbols with exaggerated attributes that leave us no doubt as to their purpose. As civilizations began to take care of man’s basic needs, the artist attained the freedom and financial support to study and advance in expressing the beauty of the body in various images: gods and goddesses, Adam and Eve, and eventually the nude for its own sake. After the re-emergence of classical realism during the Renaissance, no serious figurative artist would fail to pursue anatomy and life drawing. Only by understanding the form beneath the clothes could the artist consistently render the structure of a figure and thereby drape the…