The release of my nude drawings, “Liz II” and “Liz III” as limited edition prints by Solomon & Whitehead, Ltd. in England presents the perfect opportunity to take a fun quick glance at the nude in art.

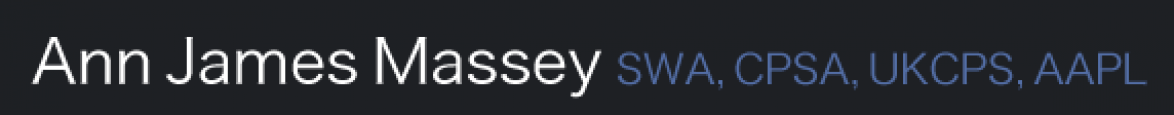

Since the dawn of man’s creative powers, artists have felt the need to depict the human form. Prehistoric sculptures were fertility symbols with exaggerated attributes that leave us no doubt as to their purpose. As civilizations began to take care of man’s basic needs, the artist attained the freedom and financial support to study and advance in expressing the beauty of the body in various images: gods and goddesses, Adam and Eve, and eventually the nude for its own sake. After the re-emergence of classical realism during the Renaissance, no serious figurative artist would fail to pursue anatomy and life drawing. Only by understanding the form beneath the clothes could the artist consistently render the structure of a figure and thereby drape the clothing accurately. As with all aspects of art, once the basics were learned, knowledge allowed the choice for deliberate distortion rather than misconstruction resulting from ignorance.

c. 25,000 BC, The National History Museum Vienna

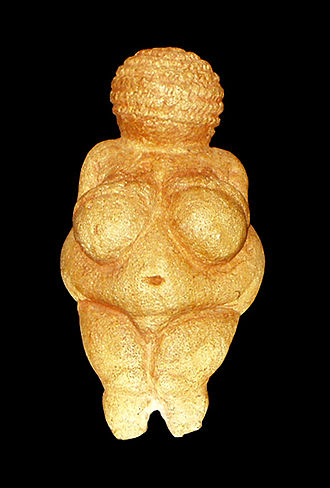

A good example would be Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) who was an adamant proponent of the importance of anatomy, even though he chose to play pretty loose with the subject, despite the appearance of tight realism. Many of his nudes seem to have two or three extra vertebrae in the lower back like the impossible torso of his magnificent “Grand Odalisque” (Louvre). And how is that leg on top even attached to the body and the arms seem not to have bones? Shown in the Salon of 1819, this now celebrated piece was attacked by critics and his fellow neoclassical artists alike for being grossly unrealistic. Looking at this work and his other nudes, especially the interesting curve of some throats (see right), it’s apparent that that Ingres was considerably more interested in the sensuous line than absolute realism in his own work despite his dictum “Drawing is the probity of art.” He blended Raphael, mannerism, and Neoclassicism into a stunning style that can only be called Ingres.

Musée du Louvre

The only surviving nude by the sublime Velazquez. Note his love too of the sinuous line, but in a more anatomical (if also not completely accurate) fashion.

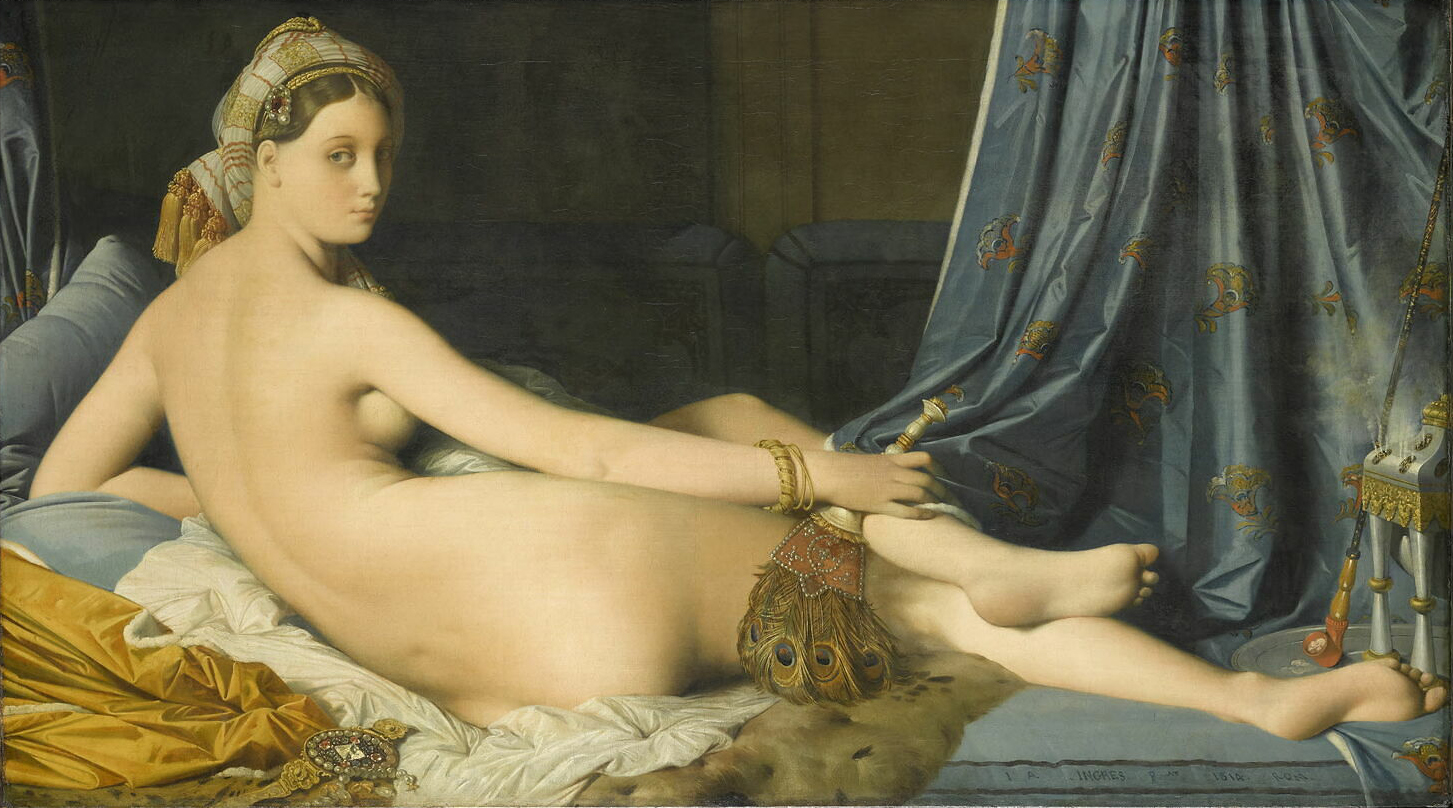

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres Musée Ingres Bourdelle

I was intrigued to see an exhibition of Ingres’ drawings at a show sponsored by EDF in Paris that displayed some of the preliminary sketches to his paintings. Most “revealing” was the fact that he drew the majority of his classical subjects nude (as have many of the great artists) before clothing them in subsequent drawings for the final painting.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres Musée du Louvre

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was another artist whose dedication to mastery of anatomy, among other aims, that also put him at odds with his patrons and the public.

Drawing inspiration for the position from Michelangelo’s Dying Slave, in 1877 Rodin created The Age of Bronze after spending more than a year doing studies of Private Auguste Neyt, a young Brussels soldier. The result was so astonishing that he was accused of having made a cast of the young man…so much so, he had photos made of the model to prove the deliberate differences and that his work was most assuredly original and created entirely by hand.

The Société des Gens de Lettres commissioned Rodin to create a monument to Honoré de Balzac in 1891. Thus followed his seven year struggle to represent a squat, overweight, physically unattractive man, involving over 40 studies and casts (including a series of nude Balzacs). In 1893, the Society came to his studio and “saw a raw clay model of what seemed an obscenely naked, gross, potbellied wrestler.” There was talk of suing Rodin for the return of the advance, though the more liberal members convinced them to give the artist more time. Nonetheless, all his studies and even the final piece resulted in controversy and public ridicule. When Rodin presented the final plaster of Balzac at the Salon of 1898, “what he believed to be his masterpiece was vilified as ‘a snowman,’ ‘an obscenity,’ ‘a toad in a sack,’ ‘this lump of plaster kicked together by a lunatic,’ and proof of the ’degree of mental aberration we have reached’ at the end of the 19th Century.” The commission was withdrawn, but supporters set up a fund to pay him the original fee and donate the statue to the city of Paris. In the end, depressed by the entire affair (and perhaps the end of his actual affair with Camille Claudel), he chose to keep the Monument to Balzac and it was never cast in his lifetime.

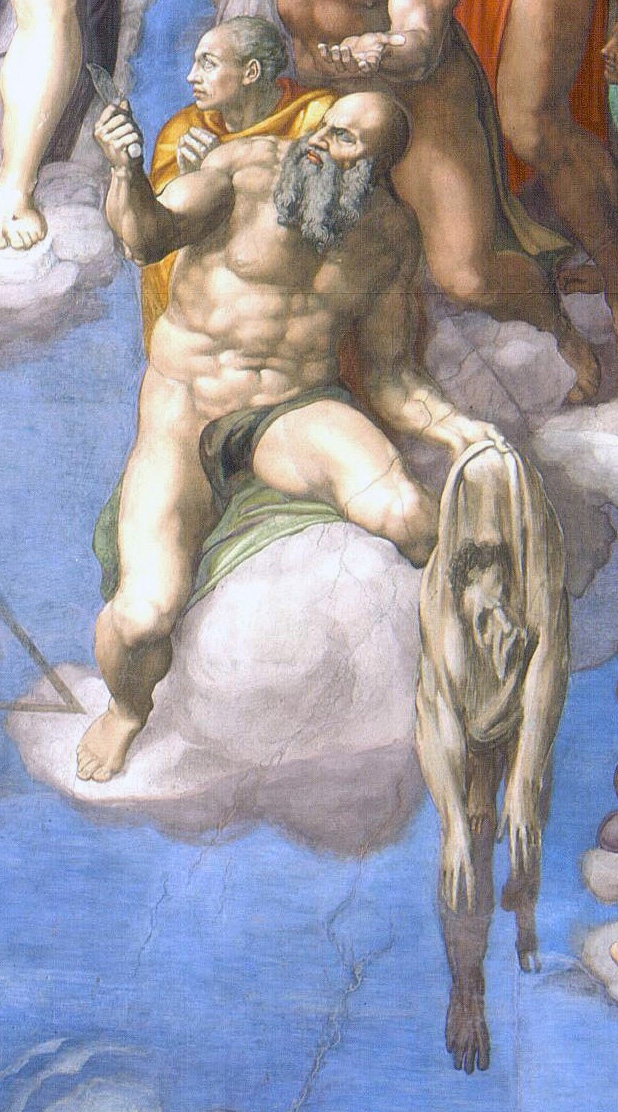

Religious art has given us marvelous nudes, but not without instances of censorship. Who can forget the one of the best-known controversies: Michelangelo’s (1475-1564) “Last Judgement” (1536-1541) in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican. Pope Paul III (Pope 1534 – 1549), who had commissioned it, was so affected by this masterpiece, that he said, “Lord, charge me not with my sins when Thou shalt come on the Day of Judgement.” However, this huge fresco, rife with nudes and facing the viewer, was pretty overwhelming to the subsequent Popes and believers in that period of the Counter-reformation. N. Sernini wrote “…the Very Reverend Order of the Chietini are the first who say the nudes do not look right in such a place, that show their bareness…” and Pietro Aretino wrote scathingly to Michelangelo that “your figures would have been better in a delicious bath.” Surprisingly, at the same time as the action against Paolo Veronese’s (1528-1588) “Feast in Levi’s House” (which did not have nudity), the tribunal of the Roman Catholic Church found “The Last Judgement” to be “correct in as much as humanity will have to appear naked before Christ the Judge.” Despite that endorsement, the sheer density of the nudity had so disturbed subsequent Popes that by the time of Michelangelo’s death, they had Michelangelo’s own follower, Daniele de Volterra, among other artists, cover the offending areas with ridiculous little drapes of cloth. Volterra became known as “Il Braghettone” (The Breeches Maker) for his part. One can only hope that with the restoration of the chapel’s ceiling now complete, the Vatican will turn to “The Last Judgement” and, just as they found Michelangelo’s original colors in the former, they will find his original figures in the latter. But then again, maybe even the faithful today would be more than a bit disconcerted facing a whole wall of nudes, as opposed to a whole ceiling of nudes that are a little more difficult to take in fully.

1536 – 1541 Michelangelo

Sistine Chapel

Right: The Last Judgement with over 300 figures, the majority of them originally nude as painted by Michelangelo Sistine Chapel

For the most part throughout history, the nude was portrayed in a credible environment such as the Last Judgement, Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden before the Fall, Bathsheba bathing, Greek and Roman deities, divinities and subjects from other religions and civilizations, figure studies, and eventually anyone in involved in personal hygiene or intimate pleasures, etc. But when nudes were portrayed in inappropriate settings, especially if there was no moral attached, they became the subject of public outcry. Just as often, changes in artistic styles depicting the nude spawned harsh criticism. Edouard Manet (1832-1883) unintentionally combined both offenses with two of his most famous paintings.

Manet’s “Luncheon of the Grass,” was inspired by an engraving of Raphael’s (1483-1520) “Judgement of Paris” and a young Titian’s (1477-1576) “Concert in the Countryside” (originally attributed to Giorgione).

With two other paintings by Manet, it was exhibited in the famous Salon des Refusés consisting of rejects from the official salon in 1863. By drawing from the Raphael composition so closely, Manet has created some odd aspects in his painting, such as a feeling of detachment among the characters with none looking at one another. The background has the appearance of a stage setting. Titian’s creation portrays nude women with clothed men, but the women are unseen muses giving inspiration to male musicians in a pastoral setting. By contrast, Manet shows one naked and another partially clothed woman having a picnic in the woods with two men in stylish modern dress. The public outrage was further fueled by the disarray of clothing and food in the foreground, the bold stare and slight smile by the nude woman directed toward the viewer, and Manet’s bold flat style compared to the popular romantic and academic styles. In essence, the painting presented no credible reason for the nudity and the women’s comportment could only indicate loose morals.

Though Manet never planned to be a protagonist, his “Olympia,” based on Titian’s Urbino Venus, and exhibited in the Salon of 1865, fared even worse than its predecessor.

Two policemen had to guard the painting to keep it from being physically attacked by irate spectators (the French are never mundane in their opinions on art). The model, with the black cat at the foot of the bed and the maid presenting flowers from an admirer, was perceived as a prostitute and common looking (unthinkable). Edmond About demanded the “gallery be fumigated to free it from the painting’s corruption.” Once again, Manet’s style was a favorite theme of the critics who blasted him for his lack of modeling and color. Paul Mantz described the outline of the body as having been “drawn with soot.” Halfway through the exhibition the painting was removed from its prominent position and rehung in an inconspicuous area above a huge door.

Certainly Manet’s “Olympia” was no redolent Venus as in Alexandre Cabanel’s (1823-1889) “Birth of Venus” which was exhibited in the Salon of 1863 (the same year as Manet’s “Luncheon”) and purchased by Napoleon III. It’s ironic that while Manet is a household name today, the immensely successful French Academic painters like Cabanel, Adolphe William Bouguereau (1825-1905) and Jules Joseph Lefebvre (1836-1912), having fallen out of fashion. were almost unknown in the USA in the 20th Century. Fortunately, the 19th Century realists, with their traditional emphasis on accurate drawing, have been experiencing a recent revival.

The most successful painter of nudes in Victorian England was Lawrence Alma-Tadema. In that laced-up era, nudes were once again only accepted in the proper settings: Garden of Eden, Last Judgement, and Antiquity. Alma-Tadema became the high priest extraordinaire of portraying the ancient past, with Roman baths as the perfect location for the genre. So well researched and executed were his paintings that they became the inspiration for the set designs in the movie industry’s “sword and sandal” epics that followed. His attention to detail plus his masterful rendering of flesh, marble, animal skins, essentially all aspects of the imagery made him the highest paid artist of his period in England. The popularity of his work faded with the rise of modern artistic trends but the pendulum has swung back to appreciation of the 19th Century Victorian and French Academic works.

Lady Lever Gallery

Another piece that survived the storm of controversy and is recognized as a masterpiece today is Jean Baptiste Carpeaux’s (1827-1875) sculpture group “The Dance.” It is now in the Musée d’Orsay with a copy by Paul Belmondo in the original location. Created for Garnier’s Opera in Paris, it is an extraordinary celebration of movement, beauty and joy. The public viewed it somewhat differently upon it’s unveiling. One spectator even threw a pot of ink at it, hitting the thigh of one of the offending figures. C. A. de Salelles, representing the “associations in favor of morality and philanthropy,” wrote in a diatribe against the piece that though he admitted it was an artistic tour de force, the women cavorting about “…smell of vice…(and) reek of wine.” Standing in front of the Opera today and looking at the four sculpture groupings, one only notices the vivacious “Dance,” while the other classical compositions seem stilted and bland.

Left: The original is now in the Orsay Museum with a cast of it in front of the Opera Garnier

What about nudity in paintings that did not stir as much controversy at the time, but seem still quite strange upon reflection. Though I am an enthusiast of Jacques Louis David (1748-1825), I am amused by his heroic “Rape of the Sabines” in the Louvre. Perhaps he anticipated this response because he published a booklet with the painting stating “the importance of deriving inspiration from ancient art and of representing the nude in painting.” Even so, I can’t imagine any self “protecting” warrior would be happy clad solely in a helmet, arm shield and sword.

As I take friends around Paris, sharing the wealth of artwork, I often find a perfect moment to ask my companions if they know the difference between the terms nude and naked. That moment usually comes while standing in front of Gustave Courbet’s (1819-1877) “Origin of the World” at the Musée d’Orsay. This unusual piece, acquired by the museum in 1995, has meant that Courbet’s paintings hanging on either side of it have never been so scrutinized by American wives, while many bored husbands find renewed interest in the “arts.” Kenneth Clark offers the explanation that most people perceive nudes in the classical manner, idealized with no body hair…otherwise the image seems naked.

Some years ago, I was repeating this gem of wisdom to my uncle, Tom Moore, who had been a cartoonist with Archie Comics. He confided to me that he knew of the perfect example of the difference between nude and naked. In 1936, the new stadium built specifically for the Olympics in Rome was enhanced with nude statues depicting all the sports: discus, javelin, running, etc. One of the modern sports participating in the Olympics that year was baseball. Laughing, Tom said, “The discus thrower was obviously a nude, but that baseball player was naked!”

The passage of time and our familiarity with the controversial artwork of the past have allowed us to accept and appreciate masterpieces and popular works without question. Somehow, I just feel that for me, the statue of the baseball player will never transform into a nude. But then again, time will tell.

Originally printed in the “Massey Fine Arts” newsletter Vol. 6 No. 1, Winter © 1998, 2022 by Ann James Massey, SWA, CPSA, UKCPS, AAPL

Support the Artist

If you enjoy Ann’s artwork, articles, or anecdotes and would like to support her with a donation, please feel free to do so here.