Grand Palais, Paris, October 18, 1996 – January 20, 1997

I admit it. This exhibit was not high on my list of priorities. Tickets were not purchased the minute they went on sale, unlike for the Vermeer exhibition in the Hague. Though I visited New York and MOMA while the exhibition was there, I never entertained the idea of viewing it. Time was too precious, and the truth is…Picasso’s work just has not spoken to me.

However, when Picasso & The Portrait arrived at the Grand Palais in Paris, October 18th, I found myself in line that very afternoon. No, Picasso’s spirit did not visit and convert me in the night. Granted, being mildly interested, I was sure to visit the exhibit eventually. This unplanned immediacy came about because I had wonderful friends, Hal Marcus (an artist also) and Patricia Medici, visiting from El Paso, and the exhibit was important to them. Just because Picasso has not held conversations with me does not mean that he has not chatted heart to heart with others.

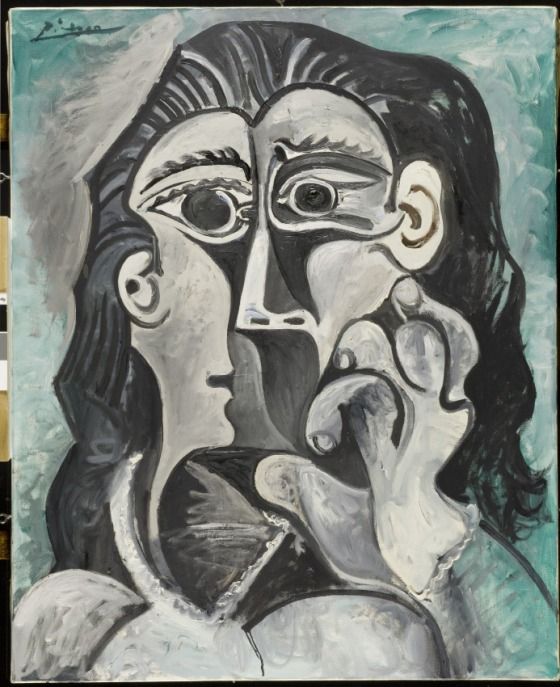

Portraiture is a misnomer here. Picasso was no portrait artist in the accepted definition: an artist’s representation of the outer and/or inner portrayal of someone. The works, even his more traditional pieces, seem to depict mask-like qualities, giving more of a sense of his virtuosity in style and ability than an insight into the individual. We may glean a little about his sitters, but we learn far more about Picasso, the artist, the “genius,” and the grand manipulator. What is not said is brought out in a huge array of photos and text, filling in the gaps where the painted images have not explained.

The exhibition borders on voyeurism. All the women are there, as are the other people important in his life. His draftsmanship is apparent, as always, in his early works. His inventiveness is easily apparent in the ever-changing styles. Evident too, is the weakness of becoming a parody, or at best, boring, in the endless repetition of an idea. It should be there, as it is part of his legacy. As he himself admitted, the sheer quantity of his production (purported to be around 50,000) illustrates the old saying that no one is a genius every moment. After all, with his fifteen variations of Delacriox’s Women of Algiers, one thinks only of the original Delacroix, and very little of any inventions by Picasso.

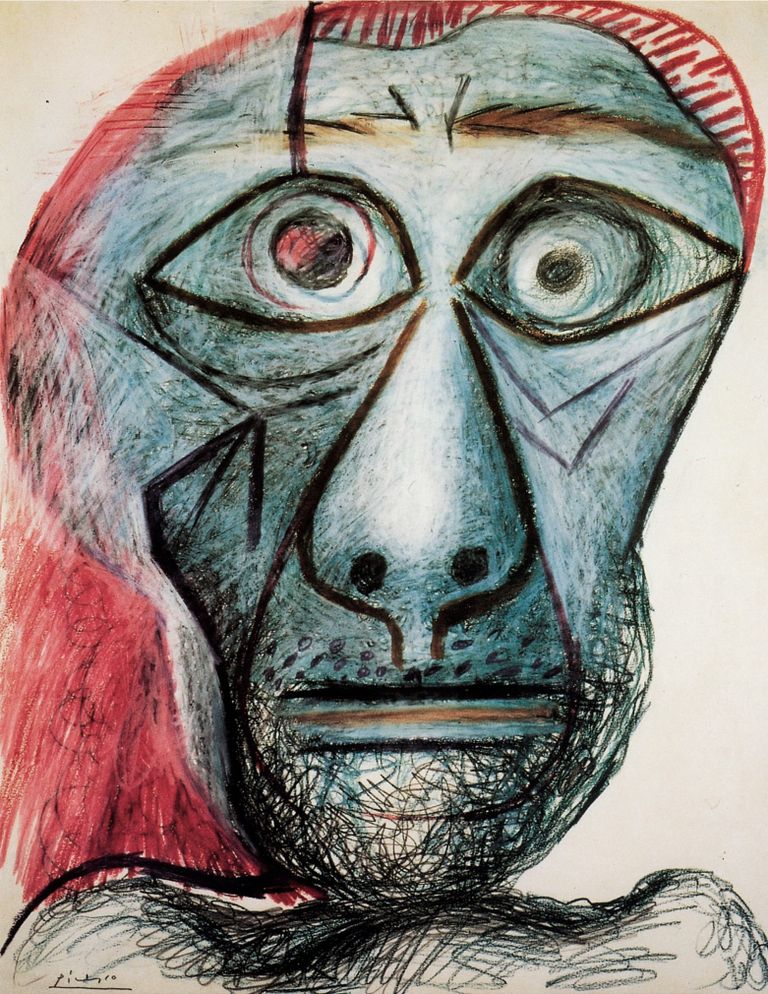

But it is the women in his life that keep reappearing in the exhibit. These women, wives, and mistresses, emerge like the plot line of his life. There are the mostly happy curves and colors, with the banana like nose, which depict Marie Thérése Walter. The blank visage of Olga Khokhlova and the sad, tearful counterpart of Dora Maar are included. They are all there, the many women he controlled and loved and often despised. As he once said, “Women are goddesses and doormats.”

Marie-Thérése, 17, was discovered by Picasso, then forty-five, as she was emerging from the Métro by the Galeries Lafayette in Paris. She knew nothing of the painter, but he knew she was his vision. Few could resist the charm of Picasso. On her 18th birthday, she became his mistress. No intellectual giant, she was his great sexual fantasy: compliant, devoted, young, athletic. Built solely on the physical, it could not last…but then, except for his final relationship with Jacqueline Roque which lasted 20 years until his death, Picasso never kept anyone more than ten years anyway. At 25, Marie-Thérése bore Maya, his daughter; but now, Dora Maar, gifted, cerebral, had come into Picasso’s life. Still, he wrote and uttered words of devotion to the new mother; later, even falsely intimating that she was the inspiration for Guernica.

There was a scene Picasso had described as one of his choicest memories. Marie-Thérèse came to his studio while he was working on Guernica. Dora, his new muse, was with him. The two women knew of each other’s existence, of course, and many words followed. Finally, Marie-Thérése insisted that he must choose one or the other. Picasso, being quite satisfied with things as they were, had no desire to pick one over the other. He told them to fight it out between themselves. And so, they did, while Picasso returned to his painting. James Lord in his biography Pablo Picasso aptly described the irony and sadness of the situation, when he commented that there were the two mistresses of Picasso, “engaged in a fist fight in his studio, while he peacefully continued to work on the enormous canvas conceived to decry of horrors of human conflict.” Was this an actual event? Most likely not as Dora Maar and even Picasso himself later denied it, but the chaos he created for the six main women, among others, in his life was very real.

A telling footnote of his grip on others came four years after Picasso’s death and more than forty after their affair was over. Marie-Thérése Walter hanged herself. Maya, their daughter, described her mother’s reasoning: her mother felt “she had to look after him – even when he was dead. She couldn’t bear the thought of him alone, his grave surrounded by people who could not possibly give him what she had given him.”

Ten years later, Jacqueline, Picasso’s second wife and married to him at the time of his death, confirmed by phone to the director of the Spanish Museum of Contemporary Art in Madrid that she would attend the opening of the Picasso exhibition ten days hence. That night, she lay down in her bed and shot herself.

These are but fragments of his life that came to mind as I walked through this exhibition. The art, the photos, the history speak of much more. With living legends, there is always too much written, shown, and said, during their lives and after. There is no denying his impact on the twentieth century. Was he a genius? Is he one of the “great ones”? Will history venerate him? I am no judge; I only have my own opinion. History, with its advantage of distance, is the ultimate judge.

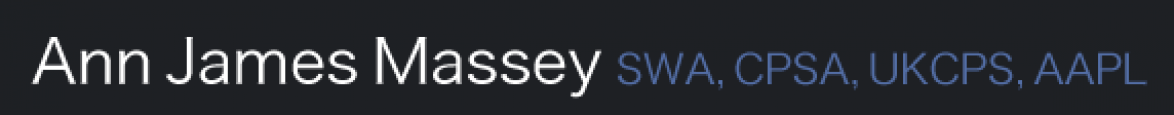

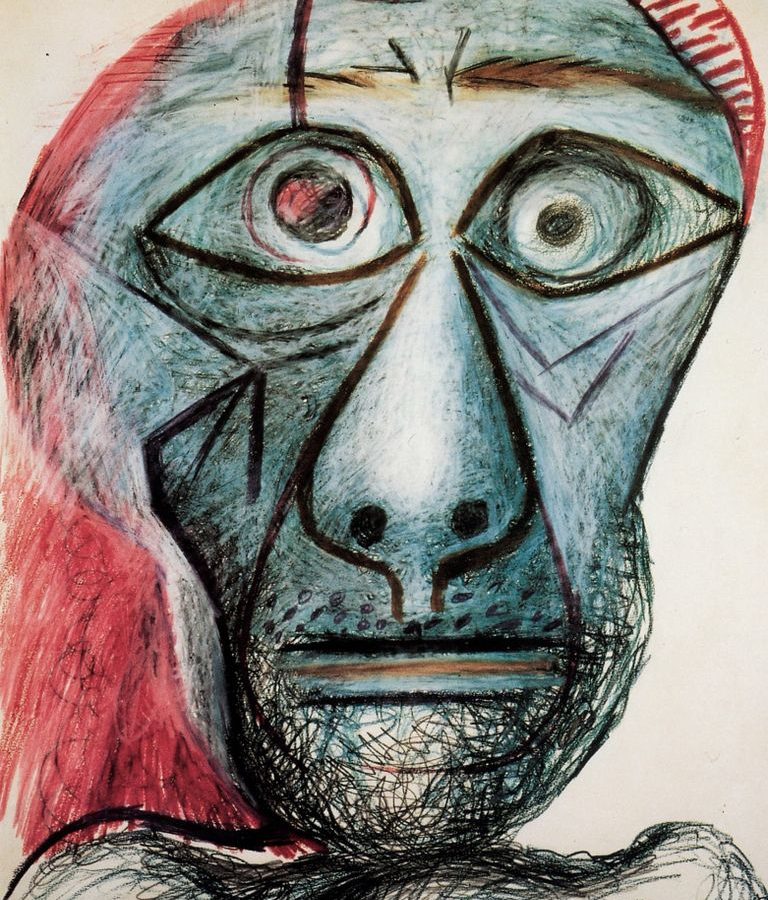

As I reached the final room of the exhibit, I came to Picasso’s last self-portrait, simple, almost apelike, drawn the year before his death. There, I caught my breath, and tears sprang to my eyes. I stared into the last mask, which, contrary to hiding the emotions, screamed them silently at me with those bulging eyes staring back…terrified. Picasso now had something to say to me; and I cried and felt pity al his last vision of himself.

Originally printed in the “Massey Fine Arts” newsletter Vol. 4 No. 1, December © 1996, 2022 by Ann James Massey, SWA, CPSA, UKCPS, AAPL

Support the Artist

If you enjoy Ann’s artwork, articles, or anecdotes and would like to support her with a donation, please feel free to do so here.